A Profound Game Introduction, and StrategyIt is expected for a person to at least know how to play Hopscotch before reading here any further. The first section herein tries to fundamentally answer the question, “What is this game?”, and the second section is dedicated to strategy. “Wild Chess” Of the two words I have used to give these games an informal name, I choose the word “Chess” to embody my sense of the thing at the start. It is a board area, made of a matrix of rows and columns, with pieces upon it, and as we play, we will be orchestrating the movement of these pieces across this matrix. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

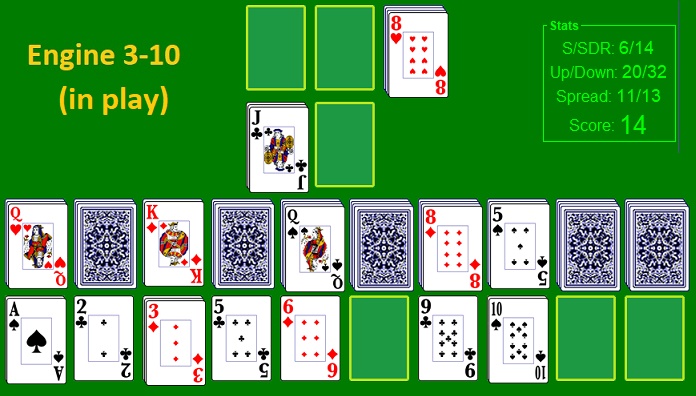

The Game Engine: The innovation of player-selected ranks in ascending order across a fixed width is what opened the gates to creating these games. The player is given the freedom, to a degree, of arranging ranks as they see fit, but within a fixed-width area. The upper and lower widths can be used to generally equal the player, within such-and-such a weight class. In 52-card Scotsi, at the start there are up to 9 x 7, or 63 options. When using 5 each of 20 ranks, or 100 cards, there are hundreds of options. I haven't seen thiese sorts of options with soltaire before. At right: The “Engine” game class is like Hopscotch, but with no slides. It illustrates the basic “options engine” that all of these games draw and build upon. A hand adds another row to the matrix (such as in the Lucky, Scotsi, and Cheshire game classes). |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

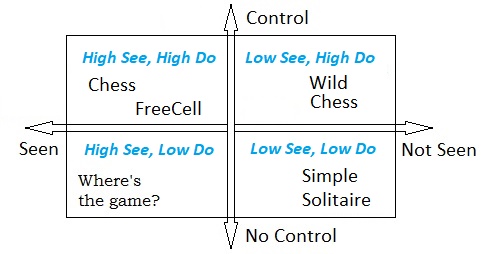

At right, I tend to define a “game” as when I don't know how it will end at the start. Today's more sophisticated solitaires (such as Spider) provide roughly 3 options. At right, FreeCell places differently with all cards face-up. As a single-player game which uses cards, Wild Chess falls most deeply into its quadrant. The portal between the player and a shuffled deck is between two infinities. When this portal, i.e. number of options, goes up, then the player is given greater access to the second infinity. Simply by shuffling the deck, this game may come to provide endless challenges and adventures. |

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Now I will try to add in the “wild” part. Chess and Wild Chess are played on flat, square boards. This game is dominated by transient elements. Imagine that the board bends, strategically, when cards flip up, sometimes to the point of seeming upside down. In my experience of making plays, flipping cards has included fundamentally altering my course in the game. I may also sometimes wonder about my current strategic orientation as a player. Luck and Skill Is this a game of luck or skill? I think you can take your pick. This may be played as a game of exploration and adventure. Scoring on this kind of play may seem inappropriate, when deliberately wandering outside of one's more tried, tested, and true ways. I think that whatever is learned from exploring can be interesting, and contribute to greater skill. Skill can be measured by recording enough scores (when trying to win) to get an average. For the game called 52-Card Scotsi, or “Scotsi 57”, I have included my scores on 30 random deals, and this is given its own section farther below. I don't think any person is going to be capable of matching this average in a short time. So long as you have not reached at least “42.7 points/game in 30 games”, then you can know there is more to learn. My scores also show “2/3 wins” (clearing all upper tableaus). Jaypegging Versus Consistency The term “jaypegging” originated from an obscure characteristic of the JPEG image file format. It has a compression algorithm that causes every decompression into memory to have a different series of byte values. Its variability is lost in the imperceptible, and its image always appears the same. In Wild Chess, to “jaypeg” is for one player to play the same “deal”, i.e. “arrangement of the cards”, a number of times when they are trying to win, and to find that they play it in a variety of ways. As an exercise, I have sat and played one deal a few dozen times, to try to see its general character. If I had a fixed set of rules for every situation, then maybe I could say that I would play consistently well. I don't know how to have a complete and fixed set of rules, so I think some filling in of the blanks are needed. Perhaps it will be good to ask, “Am I trying to experience new and different things, or am I trying to record my best scores?” Dealcodes: In the software, “dealcodes” are used to shuffle the deck. Each unique dealcode consistently produces its own unique deal. In competition, the competitors play the same deals as each other. For competition or just comparison, people can email dealcodes back and forth. A picture of your end game window can also be put to your system clipboard using the alt-PrintScreen key combination, and then pasted somewhere. Game Classes Any unique combination of items from the list below constitutes its own game class, and I have named a few. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

Game-Class-Defining Rules and Types of Plays (#s = rows) |

||||||||||||||||

|

Live to Lower (1 -> 4 and 3 ->4) File to Upper (1 -> 2 and 3 -> 2) Slides to Lower (1 -> 3 and 3 -> 3) * Slides to Upper (1 -> 1 and 3 -> 1) Lowerwalk Ascending Upperwalk Ascending

|

Hand to Lower (5 -> 4; 3 -> 5) Hand to Upper (5 -> 2; 1 -> 5) “trump” & “high trump” Coaxing on Upper (5 -> 1; 1 -> 5) * Coaxing on Lower (5 -> 3; 3 -> 5) * Den/Animals (5 -> 6; 6 -> 5)

* - conceived, not yet implemented. |

||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

The mentally more relieved games use one walk ascending, such as Hopscotch and Lucky. Smaller boards are also less complex. Two walks ascending gives more to think about, in Hopski, and then adding a hand makes it more complex in Scotsi, and coaxing is added to make it even more complex in Cheshire. I personally have played Scotsi for many years, and I sometimes go back to smaller boards, or larger ones, depending upon my mood. In these games, A “wild rank” is an unordered, i.e. non-ascending rank, and when used can be gathered on the player's choice of any one scoring destination on the board. For making games, the software currently includes 3 unique wild ranks; “Wilds”, “Frees”, and “Jokers”. These ranks do not stack with each other. Strategy: Around The World |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

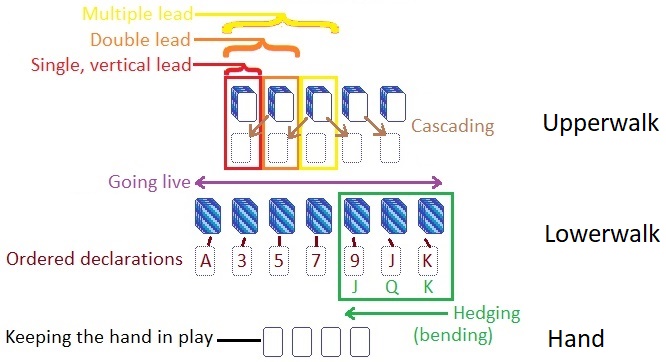

The picture above shows an “around the world” view of fundamental strategic alternatives. The Vertical Lead In the beginning of the game, all of the lower columns (and the hand) are available for scoring. The upper foundations, however; begin blocked. What this means is that 8 of 13 ranks will be able to play nicely, and the others will not. They will simply block. I call unplayable blockers “dead”. Each time a card is played from a lead stack (row 1) to the lowerwalk, the number of blocked lower columns goes up. Each time a blocker from the lowerwalk is scored on an upper foundation, the number of blocked lower columns goes down. When all of the columns of the lowerwalk are blocked, then the player is likely to be a goner. What we can know from the start is that this is like playing against a ticking clock. Each time the upper plays to the lower, the clock counts down, and when its done, generally so are we. This creates a sense of imperative – to clear one lead stack as quickly as possible – even without other plays in between, so that each time one more lead stack is cleared, one more rank can now be filed off to an upper foundation. This is what is called a “vertical lead”. In my experience, playing reminds me of the vertical lead imperative. It seems a strong force in the game, but there are sometimes other ways to find success. The Double Lead There are 4 cards in each lead stack, and 7 lowerwalk columns. Each lead stack played out to the lower will block 4 lower columns. One new foundation will become available on the upperwalk. What we have a little space to do, is to lead 1 card off of one lead stack, and then 1 card off of a second lead stack. Now two lower columns are blocked, and there are two lead stacks with only 3 cards each. This is a double lead. 5 lowerwalk columns will be blocked when clearing one of those lead stacks now. This is doable. The advantage gained was to be able to see a few more cards before deciding on which of the two leads to continue, and which to abandon, at that time. This can go another round, playing one more card off of each lead stack, blocking two more lower columns. Now each lead stack has two cards in it, and there are four blocked lower columns. Not bad? With one more play, a lead stack can be reduced to its final card, with nothing hidden underneath. The Multi-Stack Lead Multi-stack leading is quite risky; it can easily block everything and stop the game. The purpose of this is like double-leading; to get a little more information before committing to which lead stack to attempt to completely clear. This can also take place when “going live”, which we'll get to, or possibly “cascading”. Cascading Cascading is an interesting contribution to clearing lead stacks. What happens here is that the player purposely empties one lead stack, so other lead stack cards can play to it. I don't have a picture on hand, but I have seen what I call “inversions” before, where row 1 is completely cleared after only about two dozen plays, which means most of the cards on the lowerwalk haven't been played yet. Clearing row 1 gets the win. Going Live Also referred to as “lateral play” and “activity”, going live means trying to find bunnies on row 3. When this happens, openings for slides become available, which can be quite helpful. In order to do this, however; one will have to keep making live plays to the lowerwalk until four-of-a-kind has been accumulated and a blocker cleared out, for one bunny to appear. Trying to achieve this can also be costly. In my experience, I have broadened my capacity to handle various deals by clearing my lead stacks, but also by mixing in more live plays. Going vertical is a general imperative, but going live may also help from time to time. Finding bunnies on row 3 makes places to draw off cards from the current lead stack as well.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

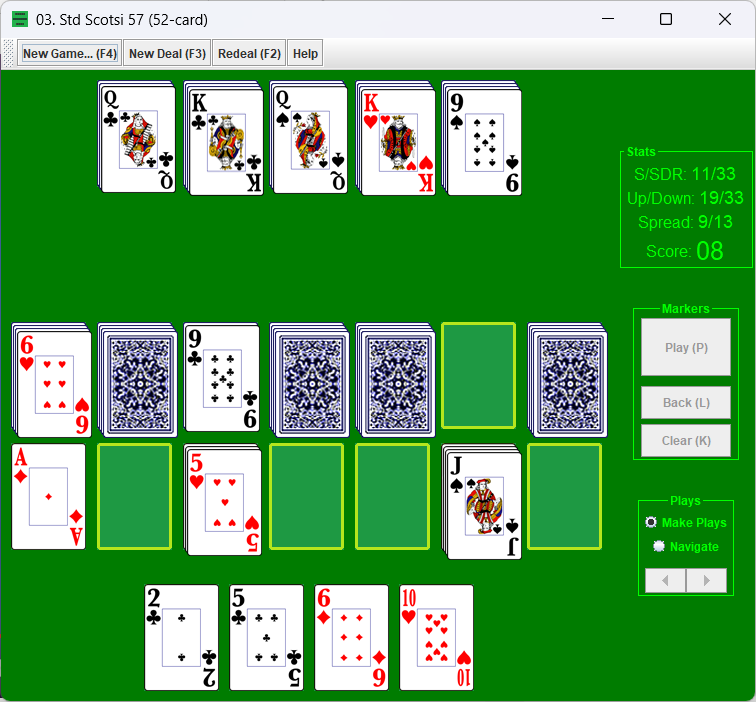

Here is a picture from a case of playing what I would have to call “extreme live”. There is a 5 in the hand which will help find another bunny on the lowerwalk. At this point, not even one lead stack has been cleared. This unusual arrangement is one example of why I call this game “wild”. It just so happens that a bunch of 5s and Jacks flipped up, so I played them. This game went on to 52 points at the end.

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Ordered Declarations 52-card Scotsi has a very nice set of ordered declarations. These are the ranks that on average will play best to a preassigned distribution of ranks across the walk. Ordered declarations for 7 lower columns in a 13-rank deck are; Ace, 3, 5, 7, 9, Jack, and King. Before seeing any cards, this is the best guess at average rank distribution, keeping equal spaces open to the left and right of the column of consideration. Hedging If we stick with ordered declarations, then we could start by declaring 3s on the second lowerwalk column. What can happen next is called a “pandora”. If the lead stack with the 3 on it also has an Ace and a Deuce in it, then those two ranks will not fit to the left of the 3, and the lead will be blocked. A blocked lead can be very nasty, and this can be as simple as playing 6s next to 8s on the lower, and flipping up a 7 on the lead, which will not play. If we see a bunch of face cards, we could declare Kings at the right, Queen next to them, and Jacks next. Each time we do this, all of the ranks in the deck will still play. With J-Q-K on the right three columns, there are four columns left for anything from Ace to Ten. Keeping every rank playable can keep the game alive. We can also think of hedging as finding “affinities”, or clusters of adjacent ranks, such as 7s, 8s, and 9s, for example. Declaring 8s, we can then play the 7 on its left, and the 9 on its right, and with space left over on each side, every rank in the deck can still be given a home on the lowerwalk as it currently stands. “Bending the board” is an interesting effect of a heavy usage of hedging. When both walks are ascending, playing all the high ranks to the lowerwalk also means the next higher ranks may be pulled all the way to the right on the upperwalk. Keeping the Hand in Play A four-card hand can be considered to be made of “four hand slots”, and each slot has a lot of power. Open bunny locations on rows 1 and 3 are also referred to as available “slots”, as are single, undeclared foundations on rows 2 and 4. In Scotsi, hand slots have the power to remove blockers from both walks. The hand is what caused me to coin the term “polyparadox”. Hand slots are capable of operating in four capacities. 1) They can play live on the lowerwalk, 2) they can make trump plays to the upperwalk, 3) they can score in the end, and 4) they can hold debris, a.k.a. garbage, a.k.a. dead cards that haven't been given homes anywhere as of yet. The hand acts as both a source and destination. It can hold cards that play to the upper and lower walks, and it can be used to hold the player's choice of one scoring rank for the end of the game. Be aware that as soon as you start picking up scoring cards in the hand, that those hand slots will no longer have the power to make plays. Tossing Tossing is when the player does something that makes it so that a perfect game cannot possibly be scored. This goes as far as ending with some garbage in the hand, or from declaring columns such that it is simpy not possible to play the ranks to the walks as declared by the player. I have a couple of pictures here from a somewhat extreme example of tossing. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

(At left) There is no way to score 4s, 5s, or 7s on the walks. Why would anyone do this? The answer most likely is, “because they had to”. It looks to me like the 8s were forced into their slot because for some reason there wasn't a play that wouldn't end the game quickly. Tossing is a choice that a player makes when they decide that a perfect game is no longer in any way feasible, and so what they will do is deliberately toss, because they will make more plays and score more points. This is an interesting added potential point of divergence in how players handle their situations. The Spread The “spread” is how evenly distributed the ranks are. If all of the ranks are very evenly distributed, then the player will be most incapable of a win. One may have to do what one can to get what points one can get. Weight Classes Don't be discouraged by a deal you can't win. These games have “weight classes”. These classes do not currently have exact definitions. When a Boardwalk game is made, it will have its own built-in average points and winning percentage potentials. I see no way around this. A game can be created that players can win all, most, some, or none of the time. When it is all of the time, it can get quite boring. When it is none of the time, then it can be too discouraging to play. The weight class can be what it is, and the player can distinguish themselves to an extent within that. Each of these things is true. I am thankful to have gotten older now, and to have found lighter weight games than what I played many years ago. 52-card Hopscotch (“58”) was my first game, and that is a very hard game to win. Lucky Seven (57) is easier. 52-card Scotsi and Cheshire seem to be nice lighter-weight games. Here are some lightweight games I've come up with that you might like to try. Hopscotch: 48 and 59 or 5-10 (48 = 4 upper and 8 lower columns, 59 = 5 upper and 9 lower, 5-10 = 5 upper and 10 lower). Lucky: 58 (Lucky 8, with one wild rank) Scotsi: 57 and 68 (no wilds) Cheshire: 66 and 77 (I like 77 with two wilds) This software has 5 each of 21 ranks for making games. After 10s come 11s through 15s, and then the face cards, plus 3 wild ranks. When making a game, the software will use enough numbered ranks to fill in after royals and wilds, for the number of ranks you specify. This is why I note a game by its highest numbered rank (Ex: 9s, or 11s), followed by the number of wild ranks. My ScoresI have just played 30 games of 52-card Scotsi, and I'll post the scores and wins/losses here, for reference. This is the best I could do. I'm keeping them in sequential order (if that helps). |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Set 1 |

Set 2 |

Set 3 |

Set 4 |

Set 5 |

Set 6 |

||||||||||||

|

48 W |

52 W |

34 L |

27 L |

20 L |

50 W |

||||||||||||

|

50 W |

23 L |

38 L |

52 W |

48 W |

47 W |

||||||||||||

|

34 L |

50 W |

48 W |

48 W |

52 W |

48 W |

||||||||||||

|

52 W |

47 W |

47 W |

27 L |

28 L |

25 L |

||||||||||||

|

33 L |

52 W |

50 W |

50 W |

50 W |

50 W |

||||||||||||

|

= 1280 points, 20 Wins, 10 Losses Looking at 6 five-game averages, the variation was as high as 3.1 points. Looking at 3 ten-game averages, the highest variation was 1.4 points. With 2 fifteen-game averages, the highest variation was 1.3 points. I cobbled together 2 twenty-game averages from the first 4 and last 4 sets. The highest variation was 0.75 points. Using this data, I would approximate variations at: +/- 3.1 points/game @ 5 games, +/- 1.4 points/game @ 10 games, +/- 0.75 points/game @ 20 games, and +/- 0.4 points/game @ 30 games. = 42 2/3 +/- 0.4 points/game. (and 2/3 wins) Where each player plays the same deals, the variations above do not reflect those of comparing competition scores. Variations caused by variation in random deals will not be happening between scores on the same deals. Those scores may reflect variations due to luck.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||